|

General

The Origin of the Famous Norton Featherbed Frame

Hope for Norton Fiberglass Fuel Tanks

Witworth or

Withworthless

A Sidecar Primer

The Best of the Best in Texas

Return to Library Contents

The Norton featherbed frame was created around an old fashioned long stroke single

cylinder engine with a very top heavy cylinder head. The size of this engine dictated the

space between the top and bottom rails of the full duplex cradle. In retrospect the result

of this early effort enabled all kinds of engines using all kinds of configurations to be

installed ion to this versatile and robust frame. Originally, it came with a bolt on rear

sub frame which eventually got welded up particularly when the bolts came loose. Over time

there where 3 major versions of the frame. These 3 major groups came in the bolted and

welded variety.

a. The Manx racer in Reynolds 531 chrome moly.

b. The single overhead cam International in grade A mild steel.

c. The Dominator twin frames in grade B mild steel.

Then there where 2 subdivisions in category a. 16 gauge tube for the 500cc and the 17

gauge tube for the 350cc. Tube gauge is important so don't go putting a 500 in a 350

frame.

Then in category c.. in about 1959 or 1960, Norton put the old single cylinder Model 50

(350cc) and the ES2 (EaSy2, 500cc) into the featherbed to rationalize frame production. As

you can see there where quite a few variations on what looked to be the same frame. Intact

they came off the same jig. 1960 was the year the top rails where installed at the rear of

the tank. This wasn’t just an Atlas mod, it was across the board. At the same time

the tank design and its badges where changed.

Edited from the Internet

Tanks For the

Memories or Hope For Norton Fiberglass Fuel Tanks

There are three main requirements for a successful sealing job:

1. The most important requirement for sealing a fiberglass tank is to start with

a solid tank. If there are any soft spots they must be removed and replaced with new

fiberglass. If you're not into high-speed grinders and polyester resins then you're better

off chucking the tank and looking for something better to start with.

2. The second requirement is that the inside of the tank must be extremely

clean. Everyone has a different process for cleaning the following is know to work.

3. The third requirement is that the sealer used must be compatible with the

fuel types to be used in the tank. Not all tank sealers are compatible with fuels

containing non oil-based compounds. Specifically, some sealers can be dissolved by very

small amounts of alcohol such as is added to gasoline during the winter. (These are

commonly called oxygenated gasoline.) Some products such as 3M's 776 sealer appear to be a

good industrial-grade solution to the problem however, upon closer examination, the main

solvents listed are all alcohol. 3M's technical assistance people say that small amounts

of alcohol turn the 776 sealer into a big gummy ball.

One important point to remember about any product sold as a tank sealer is that they do

not cure to a hard state. You could use a polyester resin to slosh inside the tank and in

effect build up a gelcoat layer inside the tank but this would dry to a brittle hardness

and could crack if the tank flexes. Consequently most tank sealers air dry to a vinyl-like

plastic coating.

There is a product recommended by the marine and aircraft people called Randolph

Products 912 Alcohol Resistant Sloshing Sealer. This is available from aircraft repair

places. Cost is reasonable and is a good sticky industrial product full of all you

favorite aromatic carcinogenic solvents: MEK, toluene, cyclohexanone and xylene. (needless

to say that you might not want to use this in the house)

The application procedure recommended follows:

1. Drain tank and remove cap and petcocks.

2. Rinse several times with hot water and dish detergent. Throw in a handful of pea

gravel with a little soapy water and shake the tank well so that the gravel scours all the

internal surfaces and loosens up any residues. Rinse several times until all the soap is

out of the tank.

3. Seal the tank drain holes with small cork stoppers and pour in a quart or so of

white gas (Coleman stove fuel) Slosh this around and let it sit for 30 minutes to remove

any fuel dyes in the tank. Drain and let the tank air dry for at least 30 minutes.

4. Pour approximately 1 quart of MEK into the tank and slosh it around. Seal the tank

and let it sit for one to two hours. Put a handful of clean pea gravel in again and shake

vigorously. If the tank has been sealed previously, the MEK should soften any remaining

sealer and the gravel should loosen it. Drain the tank.

5. Remove the gravel. If it has loosened any crud, pour in more clean MEK and gravel

until no more residue comes out.

6. Make certain that all bits of gravel are removed from the tank. You may have to

reach in the filler hole and pull out the last few pieces with your fingers. If your

fingers are not small enough, you can shake the remaining gravel over to the filler hole

side and use a vacuum cleaner with a crevice attachment to suck up the last bits. (Don't

do this while there are still flammable vapors in the tank .)

7. If there are still little bits of crusties coming out, keep flushing the tank with

MEK or acetone until the liquid comes out clear.

8. In between filling the tank with the solvents flush it with lots of hot water. It's

cheaper than MEK or acetone.

9. Finally, after the last rinse and when the inside of the tank is dry, plug the

petcock holes with clean cork stoppers.

10. Pour in the quart of sealer and seal the filler hole by laying a piece of plastic

across the opening and closing the cap on top of it (a plastic sandwich bag of the heavier

kind works here). If you don't want to ruin your paint, make absolutely certain that you

have the tank well sealed since it will build up pressure as you slosh the sealer.

11. Shake and rotate the tank so that the sealer coats all internal surfaces and then

drain the excess into a proper bucket. Pour the excess back into the can since it can be

reused.

12. Allow the tank to drain and dry with the corks removed for 30 minutes or so.

13. Repeat the sloshing process (steps 10 - 12) and let the tank dry with all openings

uncovered for at least 24 hours - longer if the temperature is less than 70 degrees. The

instructions on the sealer only say to use two coats, however if the internal surfaces are

very rough do it about 4 times. Let the tank dry for a couple of weeks.

14. When you a confident that all the sealer has dried, clean the excess from the

threads in the drain holes with a small wire bottle brush or whatever else is handy, put

the petcocks back in using some Teflon pipe thread compound on the threads as a backup to

the paper gaskets, put the tank back on the bike and GO!

Edited from the Internet

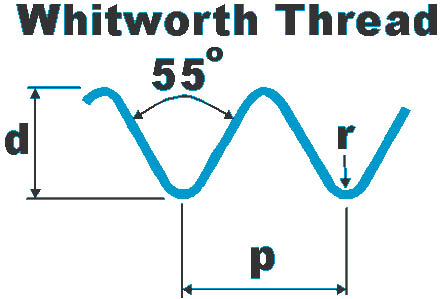

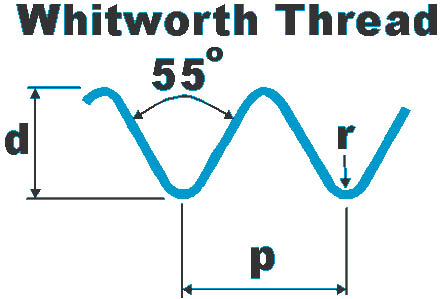

Whitworth or

Withworthless

Ever wonder why the fractional sizes stamped on your Whitworth wrenches don’t

match the size of an ordinary (US) spanner? Why use a fine vs. coarse thread? Read on.

This is more than you probably ever wanted to know. But hey, this is the age of

information glut.

By Professor Charles Falco

In the 19th Century every British factory which needed to bolt something to something

else devised their own fasteners to do it. Clearly, this caused all sorts of compatibility

problems. So, along came Mr. Whitworth (I forget his first name right now) who invented a

standardized system of coarse threads (with 55 degree thread angle and rounded roots and

crests). This standardization was a Good Thing. Along with his threads came heads for the

bolts that were based on the length along the side of one flat, rather than across

the flats. Hence, there is no simple fractional number for the length across the flats,

which is why your American wrenches don't fit. The fractional number on your English

wrenches refers to the diameter of the bolt (which is 1/4", 3/8" etc. just like

in the U.S.); not to the distance across the flats (which ends up being various weird

dimensions).

Some years later the Brits decided they needed a finer pitch for some applications, so

another thread series was introduced (same 55 degrees). They also decided that the heads

were too big for the bolts, so for most applications they switched to using the next size smaller

heads. Because of this, and to add one more bit of confusion to life, one manufacturer

will mark a particular wrench (spanner) BS 3/8, while a different manufacturer will mark

the same sized wrench W 7/16. They fit the same diameter bolt.

The first thing any fledgling Brit biker learns is that his motorcycle has

"Whitworth bolts." They think this is interesting, buy a set of Whitworth

wrenches, discover these wrenches fit their bolts, and believe they now know

everything they need to know about British fasteners. Unfortunately, at this point they

know only enough to make themselves dangerous. Instead, what they should have said to

themselves is Ohmygod, what other weird and incomprehensible things have the Brits

done to the fasteners on my machine? The answer to this question is: British Standard

Whitworth (BSW)

Sir Joseph Whitworth proposed this thread in 1841.

If

p = pitch of the thread

d = depth of the thread

r = radius at the top and bottom of the threads

then:

d = 0.640327 p

r = 0.137329 p

These are the original, 19th Century, coarse-threaded industrial bolts designed to hold

locomotives together. Because of their coarse pitch, they are more prone to vibrating

loose, so are little used on motorcycles. Except for threading into Aluminum (e.g.

crankcase studs), where a coarse thread is less prone to stripping than a fine one. It

turns out that, except for 1/2" (where the Brits use 12 tpi, and the Americans 13

tpi) the thread pitches are the same as for American Unified Coarse (UNC). However, the

thread form is different; Whitworth = 55 degrees; UNC = 60 degrees. In spite of

this, mismatched nuts and bolts mate nicely, so you're likely to find UNC bolts or studs

where BSW should have been.

British Standard Fine (BSF)

A finer pitch series, analogous to the American Unified Fine (UNF), although (unlike

the case of BSW/UNC) with none of the pitches in common with UNF. Many motorcycle

manufacturers commonly used a lot of BSF threads.

CEI (Cycle Engineers' Institute) or BSC (British Standard Cycle)

These are different names commonly used for the same threads. 60 degree thread angle,

rather than the 55 degree of BSW and BSF. For sizes from 1/4" through 1/2" by

far the most common are 26 tpi, although 24 tpi appear as well. most but by no

means all, fasteners on post-War BSA's (through the late '60's, when it got more

complicated) were CEI. Although the thread form and pitch is different, the head sizes on

CEI-threaded fasteners use the same wrenches as BSW/BSF.

British Association (BA)

47-1/2 degree thread angle. This is a metric thread system devised by the British for

small screws used in components like speedos. Not metric like you might expect, but with

diameters determined by a factor proportional to a power of the logarithm to the base 10

of the thread pitch in millimeters. I couldn't possibly be making this up. Ah, the

English. You'll find lots of BA threads on any British bike, but only for fasteners

smaller than 1/4". BA fasteners have their own set of wrench sizes. Typically, a set

of Whitworth sockets will include a 0BA (and maybe a 2BA….bigger number = smaller

size) socket.

British Standard Pipe (BSP)

A tapered, self-sealing thread system used to seal fluids (interestingly, the US and

the metric world standardized on the BSP system for threading all their pipes).

UNF and UNC

In the late 1960's, when even the U.S. was thinking of going metric, the giant BSA

corporation decided it was finally time to scrap that old 19th Century Whitworth-based

system, and switch to....yes, you guessed it, American. Since they had lots of money

invested in tooling, the switch wasn't made suddenly (or completely), so bikes from the

late '60's and later had a mix of all sorts of thread forms. Typically, engine internals

(e.g. the thread on the end of a camshaft) stayed with whatever form it used to have,

while simple fasteners (e.g. holding the fenders on) switched to UNF.

None of the Above

While the above systems account for well over 95% of all threads you'll ever run across

on a British bike, some manufacturers—again BSA springs to mind, but others were

guilty as well--couldn't restrain themselves from inventing a few oddball pitches of their

own. This is why, when dealing with British bikes, you should assume nothing. You must

have a pitch gauge and calipers.

Reprinted from the Internet

by Karl J.W. Brohan

For those of you who have ever fantasized about piloting a sidecar rig,

here are a few pointers which I have arrived at through practical experience. The

following discussion relates to cars mounted on the right side of the motorcycle.

Because the sidecar weight is not located over the Center of Gravity

(CG) of the motorcycle there is a yaw reaction about the vertical axis in reaction to

acceleration or deceleration forces.

Under acceleration the rig pulls right.

Under deceleration the rig pulls left.

These seemingly annoying characteristics can be used to enhance

cornering capability.

Right Turns

When attacking a right turn:

Decelerate prior to curve entry.

At the apex of the curve, roll on throttle and the sidecar will pull to

the right reducing pressure on the handlebars and the tendency of the car to roll around

the longitudinal axis.

WARNING!

Entering a right hand curve with a great excess of speed will cause the

sidecar to "fly" and attempt to roll counter-clockwise about the motorcycles

longitudinal axis.

WARNING!

Attempting to apply moderate to heavy braking in a right hand curve will

exacerbate the situation and the sidecar will continue to roll. An additional vector will

attempt to throw the weight of the car over the front wheel. This dramatically increases

steering effort and instability while the car is airborne. The rear wheel of the

motorcycle will unload and there is a possibility of the front wheel slamming against the

stop with highly unpleasant results. (A sidecar end!)

DISCRETION IS DEFINITELY THE BETTER PART OF VALOR WHEN ATTACKING A RIGHT

HAND CURVE!!!

Best tactic for entering a right-hander too hot:

Try to stay to the inside of the corner so you have room to runout wide

if necessary to keep car from going over the critical roll angle.

Use aggressive throttle after the curve apex and during turn exit. This

will increase turn rate without increasing sidecar roll.

Left Turns

When attacking a left turn, enter the turn with trailing throttle and

light front and rear brake. (For rigs with a sidecar brake linked to the rear brake pedal,

use light front brake only.) The severity of the curve dictates the brake/throttle

position. For example, a hard left turn: use no throttle and moderate front and rear

brake.

WARNING!

Rolling on moderate or greater throttle after the apex of the curve, but

prior to the curve exit, will cause the sidecar to attempt to pull the rig off the side of

the road, possibly sliding the front wheel to the outside of the curve and into the rough!

Minimum Radius Turns

Minimum radius, slow speed turns are best accomplished with a right hand

turn. The rig will almost pivot around the sidecar wheel with minimal steering effort

required. (one to one and a half times width of the rig)

Minimum radius left hand turns are much more difficult for you and the

rig. (three to four times width of rig) This is like trying to make a slow speed left hand

turn in a heavy B-767 with the right engine shutdown!

Steering Head Wobble

Steering head wobble is normal to some extent in all sidecar rigs. This

is most likely to manifest itself when riding at slower speeds over irregular road

surfaces. Increase steering head bearing pressure or steering damper pressure (if

installed). Usually these wobbles are momentary and do not warrant tightening the steering

head bearing pressure or increasing steering damper pressure. However, if you will be

riding over an irregular surface for an extended period, I would increase bearing or

damper pressure. Be sure to relax pressure when the surface again smoothes out.

Note: for those of you wondering how to increase steering head bearing

pressure on the fly, this is only possible on bikes with a handle on the steering head

such as older BMW's.

Additional Operational Info and Tidbits

Flying the sidecar in right hand turns is great fun, but very hard on

the rear wheel and spokes. Expect to have to tighten a rear spoke occasionally or to

replace a broken spoke. Repeated showboating can crack the rim spoke nipples.

Things to get for the tool kit:

In addition to the normal tool kit and spares items, a small bottle jack

is almost mandatory to change the sidecar wheel in the event of a flat. Extra spokes and

tubes are also handy to have.

One final Warning: If the vehicle has been parked and not under

continuous surveillance, check the sidecar wheel to ensure the knock-off hub (if

installed) has not been loosened by some prankster.

As with any vehicle, treat a sidecar rig with proper respect and you

will realize many happy miles of motoring in great style!

Karl J.W. Brohan

PS Beware, Volvo station wagons seem to be totally fascinated by the

sight of a sidecar rig and have been known to stop in the middle of the road and gawk!!

The Best of the Best in Texas

From seacoasts to mile-high mountains, Texas offers a little bit of everything

including roads you'd swear were built specifically for motorcyclists. Here's the top 10,

courtesy of Todd Nunnally and the Texas members of the Honda Sport Touring Association as

reprinted from the June issue of the AMA magazine.

1. Texas Route 118 from Kent to Study Butte: Phenomenal curves, beautiful desert

scenery and rich history in southwest Texas. The northern portion runs through the Davis

Mountains, with tight twisties, smooth sweepers and the McDonald Observatory in Fort Davis

at 6,800 feet. Farther south are the Del Norte Mountains, and farther still are the open,

desert plains of the Chihuahua Desert, where you can see forever. The capper is Study

Butte and Big Bend National Park, an out-of-the-way desert mountain region filled with

unusual lava landscapes, smooth, fast sweepers and (be careful!) strict park rangers.

2. Texas Route 170 (El Camino Del Rio) to Presidio: The ghost town of Terlingue

gives way to a spectacular 50-mile ride through lush. twisting valleys, where wind-carved

red-and-purple rock rises 1,OO0 feet off the Rio Grande river in southwest Texas.

Threading through the Bofecillos Mountains formed by two ancient lava flows, the route

takes you up a 15 percent grade at one point, winding up at Fort Leaton State Historic

Site near Presidio.

3. Texas Route 16 between Liano and Bandera: Pleasant terrain with a bonus: There

is little traffic on this 100-mile bit of asphalt heaven in central Texas. Route 16 is

full of scenic elevation changes, sweepers tight switchbacks, beautiful vistas, wonderful

tree-covered tunnels and gorgeous, clear rivers that invite the occasional wading party.

Be sure to stop in Fredericksburg, where museums and quaint shops line Main Street. And

the huevos rancheros at the Old Spanish Trail Restaurant in Bandera are tops.

4. Texas FM 337, from Medina to Camp Wood, then Texas Route 55 north to Rocksprings:

A roller-coaster ride that rips up and over huge limestone karsts recalling scenes from

John Wayne movies in south central Texas You really can't go wrong picking any of the FM

(Farm-to-Market) roads in this area, but FM 337 is unquestionably among the best. Don't

miss Last Maples State Natural Area in Vanderpool.

5. Texas FM 1431, from Marble Falls to Cedar Park: This loop around the

northeast side of Lake Travis is the tightest, gnarliest, nastiest, hilliest piece of

two-lane blacktop in Texas. This amazing central-Texas road has more converts than a Billy

Graham revival. Ride it. You won't be sorry.

6. Texas Route 4, from Palo Pinto to Granbury: Starting 12 miles west of Mineral

Wells, Texas Route 4 heading south offers spectacular bluffs and scenery through the Palo

Pinto Mountains, and it twists and turns all the way to Santo in east-central Texas. Palo

Pinto Museum boasts an Old West jail and log cabins. Don't miss lunch in the Nutt House. a

historic restaurant and restored country inn dating from 1893.

7. Texas FM 390, from Burton to Independence: Save this for one of those hot days,

and you'll really appreciate the rich ice cream at the Blue Bell Creameries in Brenham in

southeast Texas. FM 390 (get a good map) east and west from Independence offers attractive

scenery and exceptional vistas. It is especially colorful around mid-April, during

bluebonnet season.

8. Texas Route 852, southeast from Winnsboro: Typical northeast Texas-lots

of piney woods, gentle hills and curves, Winnsboro was founded in 1854 and sponsors one of

Texas' best-known salutes to fall foliage, the Winnsboro Autumn Trails. Held every weekend

in October, the festival offers sightseers self-guided tours of east-Texas forest land.

9. Texas Route 224, north from Coldspring: Located between Sam Houston

National Forest and Lake Livingston in east Texas, Route 224 is made up of hilly sweepers

and great scenery. You'll need a good map to find it, and the great U.S. Forest Service

roads nearby in Sam Houston National Forest, but your search will be richly rewarded.

10. Texas Route 762. south from Richmond to Brazos Bend State Park: This open road

through southeast Texas will surprise you with nice sweepers through the lush cotton

fields of the Gulf Coast plains. The park is a must-see 4,897 acres including the Brazos

River bottomlands, beautiful live-oak woodlands draped with wild grapevines and Spanish

moss, and oxbow lakes and marshes.

Disclaimer: The following information has been collected from various

sources on the Internet and publications for the expressed purpose of providing NTNOA

members with useful information for the enjoyment, maintenance & preservation of old

British & European motorcycles. While the information is intended to be as accurate as

possible it can not be guaranteed to be 100% correct, therefore the reader should use good

common sense and safety before implementing any of the suggestions and ask questions if in

doubt.

Copyright © 2000 NTNOA All rights reserved.

Revised: January 05, 2018

.

|